…And What Inspired Her Novel, Featuring Porcelain and Princes

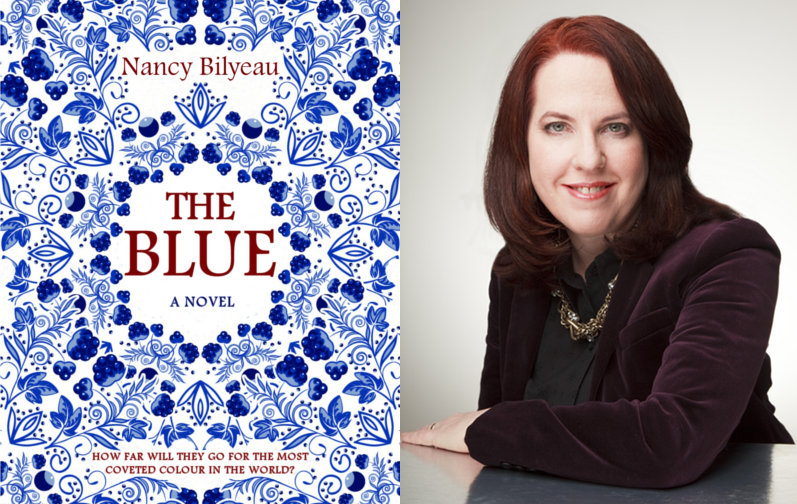

Nancy Bilyeau is a magazine editor and historical novelist. Her most recent book is ‘The Blue,’ a thriller set in the 18th century. Here she dives into her favorite corner of New York’s famed Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Deep within the Metropolitan Museum of Art stand galleries displaying such treasures and glittering décor that the sheer luxury of it makes today’s most acquisitive one-percenters seem like bargain-basement hunters. I’m talking about the Wrightsman Galleries.

Tucked between the sculpture hall and the medieval chambers on the main floor, the Wrightsman rooms display the Met’s most magnificent holdings of furniture; Savonnerie carpets; bronze, silver, and gold boxes; and, most relevant to me, Sèvres porcelain. In writing The Blue, a historical thriller set in Europe’s competitive porcelain manufactories, I found it essential to get beyond photos of Sèvres porcelain and find a way to be in the same room. One place to accomplish that was the Hillwood Estate, the Washington, D.C. home of heiress Marjorie Merriweather Post, famed Sèvres collector. Closer to home were the Wrightsman Galleries of the Met.

When you move through these rooms, you’re coming as close to a life of 18th century European luxury as you can get. And while I found myself slipping into a daze while staring at porcelain, there is another object that fascinates me too: a portrait of a 5-year-old King Louis XV (below). Now Louis XV’s taste—whether it was his own or those of his Versailles courtiers—would become a byword for 18th century Rococo. And his morals would become notorious, with his string of gorgeous mistresses, most notably Madame de Pompadour, the patroness of Sèvres porcelain.

But in this portrait he is a child, albeit one sitting on a throne wearing ermine-lined blue velvet coronation robes embroidered with gold fleur-de-lis. Why was a child made king of France, then one of the most important countries in Europe? Because France was a hereditary monarchy, and when his great-grandfather Louis XIV died in 1715, the boy’s grandfather was dead and his own parents were dead too, wiped out by smallpox. A regent, Philippe, duc d’Orleans, ruled for the boy, and it was the duke who commissioned this portrait.

Louis seems a confident child, clutching his scepter. But there was another side to him, described in a letter from an elderly female relation: “The little has plenty of intelligence, but he is an ill-natured child. … He takes a dislike to people without reason and loves making cutting remarks. I am not at all in his good books but I take no notice, as by the time he is on the throne, I shall no longer be in this world and shan’t be dependent on his whims.”

To learn more about Nancy Bilyeau and The Blue, visit nancybilyeau.com.