…And the Collection That Created a Museum

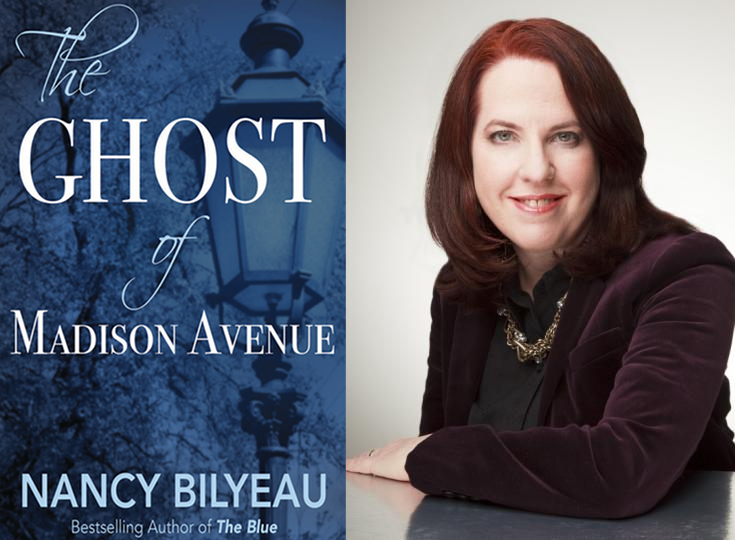

Nancy Bilyeau is a magazine editor and historical novelist. Her most recent release is ‘The Ghost of Madison Avenue,’ a novella that takes readers to J. P. Morgan’s private library in December 1912, when two very different people haunted by lost love come together in an unexpected way. Here she offers an introduction to Morgan’s art collection—which lives on today as the Morgan Library & Museum in New York City.

John Pierpont Morgan Sr. was the most powerful and feared American banker of his day, the man who financed the purchase of U.S. Steel and almost single-handedly stopped the Panic of 1907. But when he was in his fifties, Morgan’s guiding passion became collecting art and historical treasures. “Eventually, Pierpont put together the largest art collection of any private individual of his day, perhaps of any day,” Ron Chernow writes in The House of Morgan.

Unlike Henry Clay Frick and some of the other American tycoons, Morgan wasn’t trying to prove himself to anyone with his collection. He already dwelled at the top of American society and was a sought-after guest by English aristocrats and even royalty. Biographers agree that Morgan acted entirely to please himself, and he seems to have modeled himself on the Medicis and the Rothschilds. His priority was not paintings, although he owned some very fine ones; what most excited him were ancient artifacts and sculptures, rare books, and illuminated manuscripts.

One of his most important acquisitions was the Lindau Gospels, its manuscripts written by monks in the 9th century and the jeweled covers considered one of the finest treasures of the Carolingian age. Morgan’s scholarly nephew, Junius Spencer Morgan, sent a telegram in code to him in July 1899 saying that the Lindau Gospels, in the possession of the Earl of Ashburnham, could be purchased, and the British Museum could not meet the asking price. “Morgan could: He paid $10,000—nearly $50,000—for something that would be valued at millions if it came on the market a century later,” Jean Strouse writes in Morgan: American Financier.

By the turn of the century, Morgan’s Manhattan house was overflowing with acquisitions, including the manuscript of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, Rembrandt etchings, and an original Gutenberg Bible. He decided to build a private library on 36th Street, next to his house. When in New York, he spent much of his time not at the bank at 23 Wall St. but in his library’s study, its walls covered in red damask silk.

In 1906, Morgan, at the advice of Junius, hired a young woman, Belle da Costa Greene, then working at the Princeton University library, to catalog his collection and run his library. She was an enormous success. Greene organized his private library and played an active role in acquisitions, even going to great lengths to make sure that Morgan wasn’t being cheated or over-charged. He hated to haggle, and she knew that.

All the same, while he was the target of every art, artifact, and rare-book dealer alive, not all of them scrupulous, Morgan was duped relatively rarely. He had a deep appreciation for not only craftsmanship and the value of materials, but the “story” behind an object. In hearing its history, he could determine provenance. Talking to the dealer served another purpose. “He was accused of not looking at the objects,” a friend of Morgan’s once wrote, “when in reality he was looking into the eye of the man who was trying to sell it to him. It was, after all, how he had reached the summit in finance and it had paid off well.”